Contents

- 1. What is Esperanto?

- 2. What is Esperanto like? (briefly)

- 3. How is Esperanto used?

- 4. Why should I learn Esperanto?

- 5. What is Esperanto like? (in a bit more detail)

- 6. Let’s create some sentences

- 7. Word-building

- 8. Numbers

- 9. Grammatical endings

- 10. Mini-dictionary

- 11. Find out more

- Three frequently asked questions:

1. What is Esperanto?

It is a language designed to enable easy communication between people of different countries and cultures.

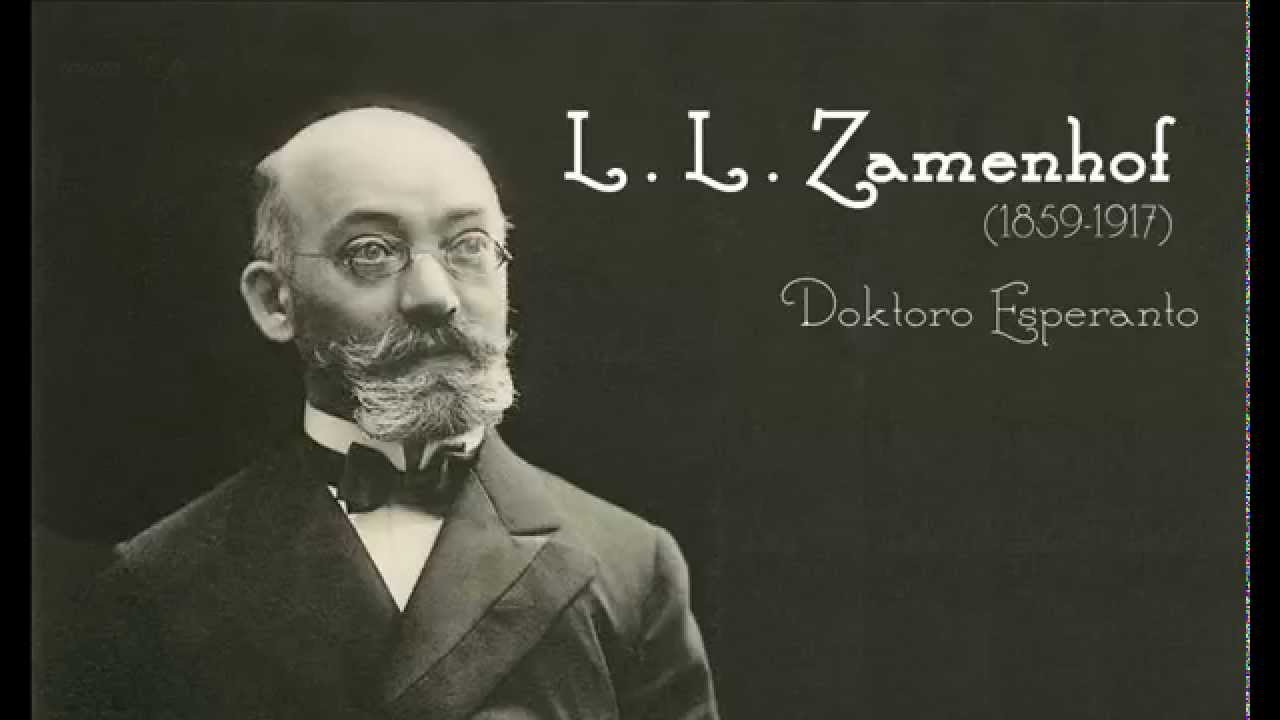

It was launched in 1887 by Dr Ludvik Zamenhof under the pseudonym “Doktoro Esperanto” (which literally means ”Doctor Hoper”)

Zamenhof called the language “Lingvo Internacia” (International Language) but people started calling it “Dr Esperanto’s language” and then, just “Esperanto”.

The basic rules and words were proposed by Zamenhof. But within a few years, people started learning it and formed a worldwide community. Since then, Esperanto has been in use (and evolving) just like any other language. So, it was founded by one man but developed by millions!

2. What is Esperanto like? (briefly)

Here are two sentences in Esperanto, about Esperanto:

‘La ĉefa celo de Esperanto estas faciligi kontakton kaj komunikadon inter homoj, kiuj ne havas komunan gepatran aŭ nacian lingvon. Ĝi estas aparte taŭga lingvo por internacia komunikado inter “ordinaraj homoj”, kiuj interesiĝas pri aliaj landoj kaj popoloj.’

In English this translates as:

‘The main aim of Esperanto is to make contact and communication easy between people who don’t have a common mother tongue (or national language). It is an especially suitable language for international communication between “ordinary people” who are interested in other countries and peoples.’

Most Esperanto-speakers learn the language as an adult or teenager. But this isn’t always the case. Sometimes people meet and fall in love using Esperanto. When they have children, naturally the first language the children hear, and speak, at home is Esperanto. It is estimated that there about 1000 native Esperanto speakers world-wide.

Esperanto is…

• Easier to learn than any national language

• Regular (there are virtually no exceptions)

• Modular (like building blocks that fit into each other: once you know a few words and basic rules of grammar you can start to create real sentences – this lets you advance very quickly)

• Phonetic (if you see a word, you know how to pronounce it; if you hear a word, you know how to spell it)

• Familiar (to anyone with any connection to a European language, including English)

• A real language (not a code: anything that can be said in a national language – e.g. Spanish, Mongolian or English – can be said in Esperanto

3. How is Esperanto used?

• Online: Email, Facebook, Twitter, Blogs, Forums, Internet chat, Skype, etc.

• Face-to-face, at meetings and congresses (local, national, regional, world)

• Travel (there is a service, called Pasporta Servo, which lets you stay for free in the homes of Esperanto speakers around the world)

• Books (hundreds of thousands of titles, both translated and original)

• Magazines (both printed and online, including a monthly magazine on politics and current affairs, often with stories not covered by mainstream, anglo-centric news services)

• Music, drama and poetry

4. Why should I learn Esperanto?

There are many reasons. Here are just four:

• For equitable international communication (without ‘A’ having to learn the language of ‘B’, or vice versa)

• Because it’s a fascinating language in its own right (Esperanto is an amazing piece of design)

• As a springboard to other languages (using Esperanto as an introduction to foreign language study)

• For idealistic reasons (working towards world peace, the brotherhood/sisterhood of humanity, etc.)

[Still not convinced? See three frequently asked questions at the end.]

5. What is Esperanto like? (in a bit more detail)

Firstly, writing & pronunciation:

Alphabet: the letters are the same as in English, except there is no q, w, x or y. Plus there are 6 letters with accents: ĉ ĝ ĥ ĵ ŝ ŭ

Most consonants are pronounced the same as in English. However:

c is pronounced ts

ĉ is like ch in church

g is always like g in get

ĝ is like g in gel

ĥ (a rare sound) is like ch in the Scottish word loch

j is pronounced y

ĵ is like s in treasure

r should be trilled (as in Italian)

s is always like s in set

ŝ is like sh in shoe

ŭ is pronounced w, but nearly always comes after a or e to form a dipthong

The vowels – a e i o u – are pronounced like Italian, or a bit like in the English sentence “Are there three or two?”

The stress is always on the 2nd-last syllable (e.g. familio is pronounced “fa-mi-LI-o”)

For more information watch this short video.

6. Let’s create some sentences

Part A

I. Choose a Subject: mi (I); vi (you); li (he); ŝi (she); kato (a cat); la kato (the cat); floro (a flower); la floro (the flower); la viro (the man); la virino (the woman)

II. Choose a Verb: estas (am / is / are); estis (was / were); ŝatas (like / likes); ŝatis (liked); vidas (see / sees); kuras (run / runs / am running / is running); kuris (ran); havas (have / has)

III. Choose an Object (for ŝatas, ŝatis, vidas or vidis): (Same as subject, but add ‘-n’. E.g. ‘la virino’ becomes ‘la virinon’.)

Or, choose an Adjective (for estas or estis): bela (beautiful); malbela (ugly); granda (big); malgranda (small); rapida (fast)

Now, make a sentence (I + II + III):

Mi ŝatas vin. (I like you.)

Vi ŝatas min. (You like me.)

La floro estas bela. (The flower is beautiful.)

Kato kuris. (A cat ran.)

Mi ŝatas la malgrandan katon. (I like the small cat.) – Notice how the adjective ‘malgranda’ takes on the ‘n’, too.

Part B: Questions and negatives

To make a question just start the sentence with ‘Ĉu’ (pronounced ‘choo’):

Ĉu vi ŝatas min? (Do you like me?)

Ĉu la floro estas bela? (Is the flower beautiful?)

Ĉu kato kuris? (Did a cat run?)

To make a sentence negative put ‘ne’ (pronounced ‘neh’), before the verb:

Vi ne ŝatas min. (You don’t like me.)

La kato ne kuris. (The cat didn’t run.)

La virino ne estas malbela. (The woman isn’t ugly.)

Part C: Plurals

To make a noun plural, add ‘j’ – after the ‘o’ (but before the n if there is one):

Katoj (cats)

Floroj (flowers)

Mi ŝatas florojn. (I like flowers.)

In a sentence, if a noun is plural, so is any adjective associated with it:

Malgrandaj katoj kuras. (Small cats run.)

La floroj estas belaj. (The flowers are beautiful.)

Ŝi havas belajn florojn. (She has beautiful flowers.) – Notice how the adjective ‘bela’ takes on both the j and the n.

Part D: Patterns in Esperanto

Did you notice some patterns in the word lists? Eg:

If ‘Mi havas katon’ means ‘I have a cat’, how would you say ‘I had a cat’?

If ‘malgranda’ means ‘small’, what does ‘malrapida’ mean?

(Answers below)

Unlike English, and most other languages, these patterns – and many more like them – are completely consistent. Verbs always end in ‘as’ for the present and ‘is’ for the past. If an adjective has an opposite, you can make it just by putting ‘mal’ before that adjective.

Answers:

I have a cat = ‘Mi havas katon’. So…

I had a cat = ‘Mi havis katon’

‘granda’ = big, ‘malgranda’ = small, ‘rapida’ = fast. So…

‘malrapida’ = slow

7. Word-building

In an Esperanto-English dictionary the English-to-Esperanto part is always much biger than the Esperanto-to-English part. Why? Because Esperanto has a clever, and totally consistent system of prefixes and suffixes.

There are 42 officially recognised ones (10 prefixes + 32 suffixes). Here are just 8:

• mal– opposite. So, ‘granda’ = big → ‘malgranda’ = small

• pra– remoteness in time. So, ‘avo’ = grandfather → ‘praavo’ = great-grandfather

• –aĵ thing. So, ‘pentri’ = to paint → ‘pentraĵo’ = a painting

• –ar collection. So, ‘leono’ = a lion → ‘leonaro’ = a pride of lions (Similarly ‘birdaro’ = a flock of birds)

• –ej place. So, ‘lerni’ = to learn → ‘lernejo’ = a place of learning, i.e. a school

• –il instrument. So, ‘kalkuli’ = to calculate → ‘kalkulilo’ = a calculator

• –ig to make something. So, ‘blanka’ = white → ‘blankigi’ = to whiten

• –ul person. So, ‘lerta’ = clever → ‘lertulo’ = a clever person

Many of them can be combined, e.g. mal-san-ul-ej-o = a place for people who are unwell, i.e. a hospital

Prefixes and suffixes are words (technically, roots) too. E.g. ‘aro’ = a collection or a group

8. Numbers

All you need to know for 1-999999 are these 12 words:

1 unu

2 du

3 tri

4 kvar

5 kvin

6 ses

7 sep

8 ok

9 naŭ

10 dek

100 cent

1000 mil

Here’s how you create the other numbers. Eg:

11 dek unu

20 dudek

27 dudek sep

102 cent du

387 tricent okdek sep

1024 mil dudek kvar

2345 dumil tricent kvardek kvin

So, how would you say 8888?

(Answer below*)

And, if you want to say 0, it’s “nul”.

9. Grammatical endings

* First, the answer from the previous section:

8888 = okmil okcent okdek ok

Here are the main grammatical endings in Esperanto:

• –o = a noun (e.g. ‘kuko’ = cake)

• –as = a verb in present tense (e.g. ‘manĝas’ = eats)

–is = past tense (e.g. ‘manĝis’ = ate)

–os = future tense (e.g. ‘manĝos’ = will eat)

–u = a command (e.g. ‘manĝu!’ = eat!)

–i = the infinitive (e.g. ‘manĝi’ = to eat)

• –a = an adjective (e.g. ‘dolĉa’ = sweet)

• –e = an adverb (e.g. ‘dolĉe’ = sweetly)

• –j = a plural (e.g. ‘dolĉa kuko’ = a sweet cake → ‘dolĉaj kukoj’ = sweet cakes)

• –n = the object of a sentence or clause (e.g. ‘Mi manĝis dolĉan kukon.’ = I ate a sweet cake. → ‘Mi manĝis dolĉajn kukojn.’ = I ate sweet cakes.)

10. Mini-dictionary

| Esperanto | English |

|---|---|

| aer-o | air |

| ag-i | act |

| akcept-i | accept |

| akv-o | water |

| al | to |

| ali-a | [an]other |

| alt-a | tall, high |

| amik-o | friend |

| am-o | love |

| ankoraŭ | still, yet |

| anstataŭ | instead of |

| antaŭ | before |

| apart-a | separate |

| aper-i | appear |

| apud | next to, by |

| artikol-o | article |

| art-o | art |

| asoci-o | association |

| atend-i | wait |

| aŭ | or |

| aŭd-i | hear |

| aŭskult-i | listen |

| aŭt(omobil)-o | car |

| aŭtobus-o | bus |

| aŭtun-o | autumn, fall |

| baldaŭ | soon |

| best-o | animal |

| bezon-o | need |

| bild-o | picture |

| bird-o | bird |

| bon-o | good |

| ĉef-a | principal |

| cel-o | aim, goal |

| cert-a | certain |

| ĉu | ? (question) |

| da | of (quantity) |

| decid-i | decide |

| dekstr-a | right |

| demand-o | question |

| dezir-i | desire, wish |

| direkt-i | direct |

| divers-a | varied |

| dolĉ-a | sweet |

| dom-o | house |

| don-i | give |

| dorm-i | sleep |

| dum | during |

| edz-o | husband |

| ekster | outside |

| ekzempl-o | example |

| elekt-i | choose |

| en | in |

| esper-i | hope |

| est-i | be |

| facil-a | easy |

| fajr-o | fire |

| fakt-o | fact |

| fal-i | fall, drop |

| far-i | do, make |

| fenestr-o | window |

| fest-o | celebration |

| film-o | film |

| fin-i | finish |

| fiŝ-o | fish |

| flank-o | side |

| flav-a | yellow |

| flor-o | flower |

| flug-i | fly |

| foj-o | turn, time |

| forges-i | forget |

| fort-a | strong |

| frap-i | hit, knock |

| frat-o | brother |

| fru-e | early |

| frukt-o | fruit |

| funkci-i | function |

| gazet-o | magazine |

| ĝeneral-a | general |

| ĝis | until, to |

| glas-o | glass |

| grand-a | big, large |

| grav-a | important |

| grup-o | group |

| ĝust-a | exact, just |

| halt-i | stop |

| hav-i | have |

| hejm-o | home |

| help-o | help |

| histori-o | history |

| hor-o | hour |

| ide-o | idea |

| inform-i | inform |

| instru-i | teach |

| interes-i | interest |

| ir-i | go |

| jar-o | year |

| jes | yes |

| ĵet-i | throw |

| jun-a | young |

| kaj | and |

| kamp-o | field |

| kant-i | sing |

| kap-o | head |

| kapt-i | catch |

| kar-a | dear |

| kaŝ-i | hide |

| kaŭz-o | cause |

| kelk-a | some |

| klas-o | class |

| knab-o | boy |

| kolekt-i | collect, gather |

| kolor-o | colour |

| komerc-o | commerce |

| kompren-i | understand |

| komun-a | [in] common |

| kongres-o | congress |

| kon-i | know |

| konsent-i | agree |

| konsil-o | advice |

| kontraŭ | against |

| kost-i | cost |

| kresk-i | grow |

| krom | besides |

| kuir-i | cook |

| kultur-o | culture |

| kun | with |

| kuŝ-a | laid down |

| la | the |

| labor-o | work |

| lac-a | tired |

| land-o | country |

| last-a | last |

| leg-i | read |

| legom-o | legume |

| lern-i | learn |

| libr-o | book |

| lig-i | tie, bind |

| lign-o | wood |

| lingv-o | language |

| lud-i | play |

| manĝ-i | eat |

| mank-o | lack of |

| man-o | hand |

| mar-o | sea |

| maten-o | morning |

| memor-o | memory |

| met-i | put |

| mez-o | middle |

| mir-o | marvel |

| mon-o | money |

| mult-a | much |

| naci-a | national |

| natur-o | nature |

| ne | no, not |

| neces-a | necessary |

| nom-o | name |

| nov-a | new |

| nur | only |

| oft-e | often |

| okaz-o | occasion |

| ol | than |

| opini-o | opinion |

| ordinar-a | common |

| organiz-i | organise |

| pac-o | peace |

| paĝ-o | page |

| pan-o | bread |

| paper-o | paper |

| pardon-i | forgive |

| part-o | part |

| patr-o | father |

| pec-o | piece |

| pens-o | thought |

| perd-i | loose |

| pet-i | ask for |

| pied-o | foot |

| plen-a | full |

| pli (ol) | more (than) |

| (ne) plu | (no) further |

| plur-aj | several |

| poem-o | poem |

| popol-o | people |

| post | after |

| poŝt-a | postal |

| pov-i | be able to |

| precip-e | especially |

| prefer-i | prefer |

| pret-i | ready |

| pri | about |

| produkt-o | product |

| proksim-e | close by |

| propr-a | own |

| prov-i | try |

| publik-a | public |

| pur-a | clean, pure |

| rakont-i | tell |

| rapid-a | fast, quick |

| regul-o | rule |

| rekomend-i | recommend |

| rimark-i | notice |

| ripet-i | repeat |

| river-o | river |

| romp-i | break |

| rond-a | round |

| ŝajn-i | seem |

| salon-o | parlour |

| sam-a | same |

| san-a | healthy |

| ŝanĝ-i | change |

| ŝat-i | like |

| sci-i | know |

| seĝ-o | seat |

| sen | without |

| send-i | send |

| serĉ-i | search |

| serv-o | service |

| sid-a | seated |

| signif-i | mean, signify |

| sinjor-o | mister |

| ŝip-o | ship |

| situaci-o | situation |

| skatol-o | box |

| skrib-i | write |

| sol-a | sole, alone |

| son-o | sound |

| special-a | special |

| spert-o | experience |

| star-i | stand |

| ŝtat-o | state (polit.) |

| strat-o | street |

| stud-i | study |

| sub | under |

| sufiĉ-a | enough |

| sukces-o | success |

| sun-o | sun |

| super | above |

| sur | on |

| tabl-o | table |

| tag-o | day |

| tamen | however |

| teatr-o | theatre |

| telefon-o | telephone |

| ten-i | hold |

| ter-o | earth |

| tim-o | fear |

| tra | through |

| traduk-i | translate |

| tranĉ-i | cut |

| trink-i | drink |

| trov-i | find |

| tuj | immediately |

| tuŝ-i | touch |

| universal-a | universal |

| urb-o | city |

| uz-i | use |

| varm-a | warm |

| vend-i | sell |

| ver-a | true |

| vesper-o | evening |

| vest-o | garment |

| viand-o | meat |

| vid-i | see |

| vir-o | man |

| vitr-o | glass |

| viv-o | life |

| vizit-i | visit |

| vojaĝ-i | travel |

| voj-o | way, route |

| vok-i | call |

| vol-i | want |

| vort-o | word |

| zorg-o | care |

11. Find out more

Here are just two other websites for more information (and more useful links):

• Australian Esperanto Association

• Doctor Dada

Here are two websites where you can learn Esperanto for free:

• Duolingo (also available as a smartphone app)

• Lernu!

Three frequently asked questions:

1. “Why not English? Isn’t it already the international language?”

(This is usually the first question that gets asked about Esperanto in English-speaking countries. Not so much in other countries. 🙂 )

Here are two answers:

• Esperanto is easier

• Esperanto is fairer

Although many people all over the world study English, and often think they speak it well, the number of people who can participate in a non-trivial conversation in English is very small outside English-speaking countries. Knowing English may be sufficient to survive as a tourist in many places, but not for more.

2. “Is Esperanto a real language? (Or is it artificial & therefore soulless?)”

All languages are, in a sense ‘artificial’. On the other hand, perhaps you could say that Esperanto is an artificial language, like a car is an artificial horse. Horses are great, they are beautiful, but a horse probably wouldn’t be your first choice if you wanted to get somewhere fast. But if you wanted a fun afternoon, your choice would be different. Cars were designed to be fast. Esperanto was designed to be fast to learn.

People who’ve learnt a number of languages including Esperanto, have consistently reported that they were able to learn Esperanto at least five times faster than any European language.

Many Asian people have said that they’ve spent 10+ years learning English without getting anywhere, and yet they’re fluent in Esperanto after just one year.

‘Artificial’ is good. No non-artificial language can be as easy as Esperanto. English certainly isn’t.

3. “How successful is Esperanto?”

Many people who’ve heard of Esperanto – perhaps many years ago – think it’s “just a failed project”.

Can we judge its success by how many Esperanto speakers we personally meet in the course of our everyday lives (especially in Australia)? In fact you may have met some already and not realised it.

So, how many people speak Esperanto worldwide?

It’s very hard to tell (after all, what exactly do you mean by “speak”?). The Finnish linguist Jouko Lindstedt gave the following estimates (in 1996) of language capabilities within worldwide Esperanto community, based on standardised surveys in multiple countries:

About 1,000 have Esperanto as their 1st language (children of parents whose common language was Esperanto)

About 10,000 speak it fluently.

About 100,000 can use it actively.

About 1 million understand a large amount passively.

About 10 million have studied it to some extent at some time.

Also,

– Google Translate, Facebook, Firefox and Linux all support Esperanto

– The Chinese government publishes news in Esperanto virtually every day

– The Esperanto version of Wikipedia has more articles than, eg, the Danish or Hebrew version

– The Roman Catholic Church has accepted Esperanto as a liturgical language

– Hungary has had state-recognized examinations in Esperanto since 2001 (More than 35,000 people have been examined so far)

– More than 800,000 people have registered to learn Esperanto on Duolingo, a website and smartphone app.